Cet article est également disponible en : Français

In recent days, I haven’t been feeling great. First, there was a drop in my blood pressure accompanied by dizziness. Then one evening, fever and the onset of diarrhea. Clearly, I’m not as resilient as I used to be. Is it malaria? I should go to a hospital to get tested, but it’s late, and it’s pouring rain. The rainy season is fast approaching. In doubt, I decide to start taking anti-malarial medication: Coartem. I will see about the test tomorrow.

The next day, it’s Riad, the mechanic who has become a friend, who takes me to his doctor. Sitting on the back of his motorcycle, I smile. Neither of us has protective gear. Not even a helmet. Well, this is Africa. And it’s not unpleasant to ride with my hair – well, what’s left of it – in the wind.

The test is negative. But I have already started the treatment, and that could hide the infection, so I have to finish taking these damn pills for three days. Is it the medication? My blood pressure remains abnormally high this time. I don’t understand anything anymore. Will I have to return to France so my cardiologist can adjust my prescription? I’m beginning to seriously consider it.

Fortunately, Khodor, an Americano-Lebanese-Ivorian motorcyclist with his infectious joy, is here, along with his friends. In the evening, we share good times, sometimes a little too much to drink. Between two of these evenings, I also find myself chatting with the Black King and his friends. The Black King? He is a Beninese man who has lived in Abidjan for several decades. He makes his own flavored rum, which bears his name. Or maybe it’s the other way around. He also runs a small roadside restaurant, where you can enjoy excellent African dishes, such as grilled fish served with alocos for the modest sum of 3,000 CFA – about 4.5 euros. For comparison, at the ultra-modern shopping center nearby, an espresso costs 3 euros. Mathurin, the Black King’s name, is over 70, but I would have guessed he was at most 60. A nearly faded scar marks his neck, a remnant of a bullet fired by a rebel 20 years ago. In another life, he was a drummer. Today, he lives peacefully, and in the evenings, his clients and friends come to chat while drinking some of his rum, or a beer for some. On weekends, he takes his bicycle and rides to Grand-Bassam, about thirty kilometers away.

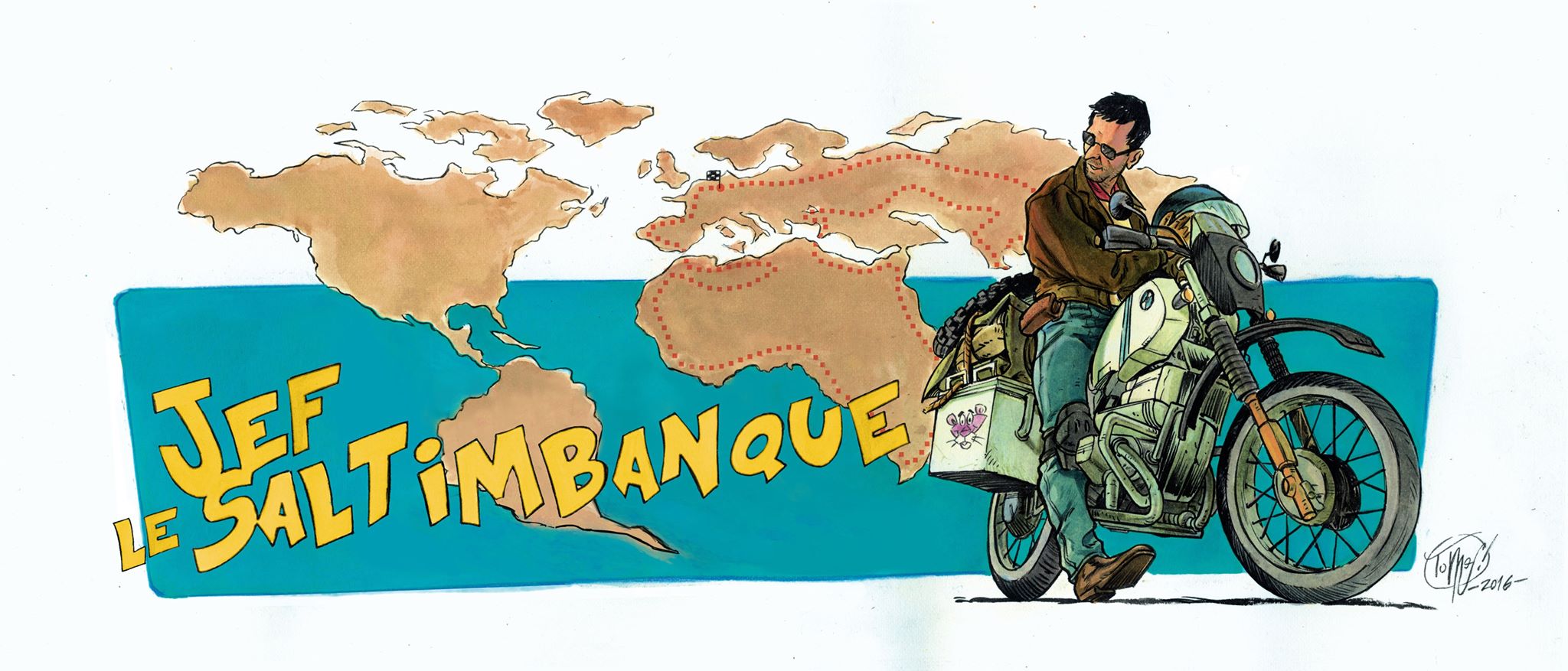

I won’t lie to you; during these days of relatively solitary reflection, I meditate a lot. Doubt has settled within me. What have I come to seek in Africa? To relive the journey of 20 years ago? That’s impossible. Africa has changed. I have changed as well. I clearly don’t have the same endurance as before. Abidjan, Baptiste, and I left more than 2 weeks ago. I had to come back for a broken tooth. Nothing serious, and it allowed me to celebrate my 62nd birthday properly in the company of the owners of the wine route restaurant. A nice bottle they provided was uncorked for the occasion, accompanied by an excellent platter of cheeses. But deep down, is this really what I came to seek? Even though I love these moments, where is Africa? My Africa? Where is the adventure?

The main roads have been paved. And social media has taken over. Information is readily available. On Facebook, you can find countless traveler support groups. On my smartphone, like everyone else, I have installed IOverlander. This app makes it easy to find mechanics, consulates, shops, accommodations, and camping spots if needed. It’s undeniably convenient, and it was this app that helped me choose the mechanic who overhauled my engine in Kathmandu a few years ago. But again, where is the adventure? Where is the unexpected, the unknown? It’s almost becoming a guided tour where every traveler merely follows in the footsteps of the one before. Tourism. I have nothing against tourism; quite the contrary. But that’s a different mindset, a different philosophy. For a moment, I think about giving up. Why not turn back and head to Afghanistan, which has been opening up to foreigners for some time?

While “chatting” with a friend on WhatsApp, he points out to me that “adventure” in English means “Adventure.” From the Latin “Ad”: to go toward and “Venturus”: what is to come.

Adventure is therefore “going toward what is to come.” That’s a good definition, and the hot air balloon pilot I am – you know where you take off, but never where you will land – does not deny it.

Let whatever may come happen, I will thus continue this adventure. But by only taking the back roads. In the evening, I consult the famous IOverlander app using the “camping and accommodation” filter, but not to determine where I will sleep. Quite the opposite: I choose areas where there are the least indications. To pinpoint the areas least frequented by other travelers, a bit like aeronautical engineers during World War II who decided to protect the places where there were the fewest bullet impacts on the fuselages of returning planes, deducing that those who managed to return were the least severely hit. Thus, I hope to find a more authentic Africa (I exaggerate a bit in writing this text; we did indeed travel through remote areas in Guinea with Baptiste, but it was too brief and too swift for my taste).

One morning, almost at dawn, around 10 a.m., the lazy person that I am finally sets off under the watchful eye of the Black King, who is there to wish me a good journey. I have decided to take the road north of Côte d’Ivoire, following the Ghanaian border as closely as possible. Once past the suburbs of Abidjan, the highway becomes a road, then a dirt road, and finally a trail. By “dirt road,” I mean a mix of paved roads, more or less potholed, and red laterite tracks. On these, the ground remains relatively dry between two storms. A few muddy spots and large puddles more or less deep, but nothing Lady Pink, my motorcycle, can’t handle effortlessly. She will only need a good wash from time to time, that’s all.

In the evening, while looking for a camping spot, I encounter a problem: I can’t find any. The region is hilly and covered with vegetation. I would need a hammock, which I do not have. So, I decide to ask for hospitality in a village and set up my tent near a church. In the morning, I chat with the master of the place. He is both a teacher for young children and a catechist in the priest’s absence.

As we converse, he informs me that the Ghanaian border is very close. I had planned to cross much further north, but out of curiosity, I check on Google Maps. I don’t see any roads in this area, let alone border posts. I check the various mapping apps at my disposal: nothing! Just forest. This intrigues me. The man is categorical: “Yes, yes, there is a border post!” His wife often goes there by motorcycle taxi for trade. It’s not very far. And getting there is simple: just take the path to the right when leaving the village, then left after a large palm grove, and finally right into the forest.

I feel a little tingling of pleasure mixed with apprehension wash over me.

An hour later, I stop at the village’s exit. The indicated path is indeed there. On my GPS, it seems to lead to a nearby village. But then, nothing, no road toward any border. I ask a woman sitting nearby: “Ghana?” She points to the famous path. I hesitate for a moment. My GPS urges me to keep going straight. But there’s this path calling to me. The adventure is there: right, left, right. It’s simple. What am I risking? Except maybe having to turn back. Mentally sweeping aside all objections, I plunge into the uncertain.

The red path winds through vegetation of a green made more vibrant by the nourishing rains. After a few kilometers, I indeed find a first junction. Soldiers are eating under a wooden hut. I ask them for directions to Ghana. One of them gestures with his head, his mouth full, directing me to the path on the left.

Pretty quickly, the palm grove gives way to the forest. At one point, as I’m heading up a fairly steep incline, I see a small truck coming towards me – the only one I’ll encounter, by the way. The path is narrow, and I have to squeeze right to the edge of a pretty deep ravine. Alas, at the moment of departure, my foot slips, and the motorcycle falls woefully. Barely standing, three young men who had just helped the truck through a small muddy patch come to my aid. The motorcycle is on its wheels in less than 5 minutes.

A few kilometers later, a barrier blocks my way. Sheltered under an open wooden hut, a few people rest, including a woman and her baby. A man in jogging pants and a white T-shirt feeds clucking chickens excited by the falling grain. As he throws a last handful, he wishes me a “good arrival,” a common welcome term in West Africa.

I am at customs. The man who speaks to me, holding an empty grain bowl, is none other than the senior officer on site. With a big smile, he invites me to sit in the shade, which I quickly do. Nearly two hours later, we are still chatting. Amid laughter, we have philosophized about the world. Westerners are rather rare here, and he hadn’t seen one pass in over a year.

In the sky, the sun continues its journey. It’s time for me to leave if I don’t want to have to camp here tonight. I take out my passport and hand it to him: “You should check it, right?” He grabs it laughing, flipping through it before handing it back to me. He doesn’t have a stamp anyway.

I leave.

A few more kilometers, and another barrier rises in front of me. This one is steel – the first was wooden – and painted blue. White letters indicate I’ve arrived in Ghana.

A shirtless man approaches me. He seems a bit surprised: what am I doing here? He nevertheless decides to open up and invites me to sit down before asking for my passport. Clearly, he doesn’t know what to do with a tourist like me. He will have to refer to his hierarchy. Unfortunately, the phone network is poorly received, and he grabs his radio. After a good half-hour, he informs me that one of his colleagues will escort me to an immigration post located at the park entrance. Finally, the exit as far as I’m concerned. This road that doesn’t exist has led me into a Ghanaian national park. As I take my leave, the man says, “You have to leave me something.” I exclaim, “Heeeyyyy, my brother!!!!” while laughing. He laughs in turn, half-embarrassed, half-disappointed, and we high-five. In my mind, I think that at this moment in the story, someone would have made an 8 million views video titled “Corrupt customs officials trying to extort money from me,” risking plunging the poor fellow and his family into misery and infamy.

For now, I follow the lead of a motorcycle taxi on which the customs officer takes a seat, escorting me to the park exit. There are three of them. The park is magnificent, and I’m impressed by the size of the centenary trees: several dozen meters high for some of them. Just after a turn, a beautiful green snake darts under my wheels. I hardly have time to be afraid before I’ve already passed.

At the park exit, the motorcycle taxi stops in front of a new wooden shack. A young man in red shorts quickly puts on a green T-shirt indicating his function before coming to greet me: Immigration.

He seems just as uncertain about my case as his colleague on the other side of the park. He tells me to wait for 5 minutes. I reply that I have all the time in the world, but that beyond 30 minutes, he will owe me a soda. He laughs.

A few moments later, he tells me that I must continue down the path until I reach the road. Agents will wait for me on a motorcycle to escort me to the customs office where I can have my passport stamped to confirm my entry into the territory. After a few discussions about travel and my motorcycle, I get back on the road. Finally, the path.

For now, I am still clandestine on Ghanaian territory.

But not for long; upon arriving on the paved road, I actually find two men who wave for me to follow them. A few minutes later, we finally arrive at the famous post. In an office, two men and a woman greet me as I enter. The conversation starts cordially but quickly transitions to usual questions: who am I? What am I doing? Where am I going? Very quickly, the tone shifts from cordiality to outright laughter. A crazy white person traveling across Africa on a motorcycle! One of the customs officers finally grabs the long-awaited stamp and politely informs me that he’ll stamp it in a corner to save me a page. Unfortunately, his stamp isn’t working well, and he ultimately has to redo it on another blank page.

But I’m not yet finished. I still need to have my customs passage book stamped! It’s even more crucial since I couldn’t do it when leaving Ivorian territory. So I ask them about it; unfortunately, it’s not in their jurisdiction. It depends on another office located a few kilometers away, of course. Otherwise, it would be too simple. The officer takes his phone and informs his colleague of my presence. It’s too late for today. Despite the few kilometers I’ve traveled, the sun is already completing its journey across the sky. It’s true that I’ve spent more time chatting than riding. The man continues his phone conversation, then turns to me and asks where I’ll be staying tonight. I don’t dare reply that I had planned to camp and instead indicate a nearby hotel. A private discussion again. Then he tells me that his colleague will come to my hotel tomorrow morning to finalize the formalities. Good! No camping tonight, but a nice hotel with a pool. Life is indeed tough.

“Going toward what is to come” and keeping the door open to possibilities. That’s the adventure. No more, no less.

Written on June 1, 2024 – Forest Camp of Boin National Park – Ghana

No Comments