Cet article est également disponible en : Français

Yesterday, on Facebook, a post by a motorcyclist recounting being attacked by Kangal dogs in Turkey took me back over 50 years.

I felt the urge to share a bit about my childhood and put on paper some traumas I have almost never spoken about. A kind of therapy through writing. I’ve been a bit introspective lately. I apologize for that; travel stories will resume soon.

During an interview, Jacques Brel said this: “Childhood is a geographical place.” That remark struck me deeply at the time because I found it so relevant.

My childhood took place in Turkey (then my adolescence in Portugal, but that’s another story).

We were a small community of French people, consisting of up to about fifty children. Our parents were “expats,” a term now somewhat overused and often used incorrectly. The term “expatriate” refers to a specific legal status. An expatriate is someone sent on a mission to a third country. They stay there for a determined period based on certain contractual conditions (often quite advantageous). An expatriate is not an immigrant. Conversely, an immigrant is not an expatriate. Nowadays, the confusion between the two is quite common. However, they are distinct concepts.

But that is not the subject of my article.

I want to talk to you about this very special childhood of mine. Well, for me, it didn’t seem so special. It was my life. End of story. Simply, when I returned to France for holidays, it seemed to me that those I reconnected with were still living the same life, with the same habits. At the same time, I had discovered a thousand things. That sense of disconnect has never completely left me.

My parents would leave at the slightest opportunity, and I was dragged between historical sites and museums throughout my childhood. Of course, in Turkey, but not only there.

At a very young age, I also saw both the Dachau and Auschwitz camps.

Overall, the life I led was more than enviable, even though we lacked many food supplies — for example, milk was delivered by a man in a cart pulled by a mule. Often, if he arrived too late in the morning, it was turned (or diluted with water if there wasn’t enough). A simple chicken had to be ordered several days in advance. And when we had a camembert kindly brought by a passing Frenchman, it was a day of celebration.

Bursa was located 30 km from the winter sports station and 30 km from the sea. I spent my winters skiing and my summers by the sea, where we moved during the hottest months. My father had one of the only two speedboats along the entire coast. I was allowed to go alone starting at the age of 13.

The rest of the time, I wandered through the countryside. Stray dogs were numerous there, often in packs. It was necessary to distinguish the “normal” stray dogs, often mangeled and always in packs. They weren’t too dangerous: you just had to crouch down as if to pick up a stone to make them flee. The young Turks were incredibly accurate—I remember a friend capable of killing a bird with a simple throw of a stone—and the dogs knew it very well. At that time, the authorities regularly carried out poisoning campaigns to eradicate them. My own dog had been narrowly saved, I will never forget that wait in the veterinary office—when the veterinarian had stepped out—while my beloved dog was convulsing in my arms. She was saved at the last moment, the antidote being known and particularly effective.

And then, there were the lords of the countryside: the Kangals, wolf killers, with cut ears and collars with steel spikes. They feared nothing and no one. When I sensed their presence nearby a flock of sheep, I would keep as far away as possible. They fascinated me, but I was wary of them.

I experienced two particularly striking episodes. The first was while skiing off-piste with my father in the middle of the forest on Mount Uludağ. Suddenly, we came across a pack of Kangals lying in the snow. It was impossible to avoid them; we had to pass within about ten meters of them, as slowly as possible, to avoid triggering their hunting instinct.

The second was a Kangal, with saliva dripping from its lips. It was quite lethargic, and we crossed paths at about thirty meters. Shortly after, soldiers arrived and shot it with a submachine gun. I then learned that it was rabid.

Cette vie encore une fois, à bien des égards enviables, n’a pas été sans traumatismes.

This life, once again, in many ways enviable, has not been without trauma.

The first, and most important, was the return. At the time, there were no studies on the effects of expatriation on children’s development. However, it was not without consequences, especially at a time when cultural differences were much more pronounced than they are today. The lack of any bonds with family—except during vacations—made the break for the expatriate child even more striking.

For me, it was incredibly difficult. Extremely so. I was completely out of sync with French society, and it must have taken me about ten years to “understand” and accept France, which I passionately hated for years. For some, it was even more severe: depression, suicide, turning to drugs, or even delinquency. These cases are relatively few in absolute numbers, but proportionally—about fifty children—it seems significant to me.

Very late, I learned that we were called TCK : Third Culture Kids. When I read—by chance—an article on the subject, everything fell into place in my mind.

Around the age of 18, I deliberately moved in with my grandmother to establish roots there.

At the time, unconsciously, all my friends were either other “TCKs” or children of immigrants, with whom I shared much more than with native French youth, with whom I always felt out of sync.

Return was not the only “trauma”; there were many others. As I mentioned, we led an enviable life—both very free and privileged. Nevertheless, the country could be harsh at times. I was faced with or witnessed scenes that few children in France would ever know.

I will share a few of these moments with you. I will start with illness.

- A friend was saved at the last moment from rabies. He had been bitten by a confirmed rabid dog. No serum was available, and he had to be urgently transported to Istanbul.

- A classmate’s father had less luck. He died of cholera in less than 10 days despite being repatriated to France.

- Regarding illnesses, at that time, very few or no people were vaccinated. On the streets, it was common to see beggars with polio sequelae—arms or legs atrophied. Since that time, I must admit I’ve been a bit annoyed by the so-called “anti-vax” movements, which seem to me like spoiled children’s whims (sorry if this offends anyone).

A bit haphazardly, there have also been:

- The “encounter” with a drifting underwater mine. These mines were used to prevent submarines from crossing the Bosphorus without surfacing. They were normally anchored deep in the strait. But sometimes, some would detach and drift away. That day, while I was swimming, I noticed a floating shape. Curious, I approached it. I should say “we” actually: I wasn’t alone that day. An adult whose name I’ve forgotten accompanied me. He quickly understood the danger, and we moved away. The device was reported (I don’t know by whom—fishermen or the man with me?) and the military quickly intervened to blow it up.

- My father, who almost was killed by a grenade thrown by “fishermen” a few seconds earlier. We were alone on a small cove. He had just come out of the water, where he had been fishing some fish with a spear. And suddenly, on the other side of a small rocky promontory, we heard a violent explosion. A few minutes later, hundreds of fish were floating on the surface, belly up.

- A classmate of mine, who, while out walking, came across the corpse of a child tied up and in advanced stages of decomposition.

One of the things that deeply shocked my childhood soul, I admit, was the status of women. I firmly believe—and will tirelessly support—that hospitality in Muslim countries is incomparable. However, I have always thought there were several aspects that needed reconsideration on this point. Starting with the segregation from a very young age—around prepuberty—between boys and girls. I personally suffered from this, even though I was French, because there were no female classmates around my age in the French community. And on the Turkish side, it was strictly forbidden.

When I returned to France as a young adult, it took me years to learn how to behave around young women. I didn’t know the “rules.”

One scene in particular left a strong impression on me. I must have been about 10 years old.

A child had been hit by a car. It was a minor incident; the little girl was only shaken up and a few adults were trying to comfort her. But there was this man—probably the grandfather—who started yelling while hanging onto a large fig tree branch. I watched him without understanding at first. He managed to tear off the branch—huge, he must have held it with both hands—and began hitting the woman responsible for watching the child (I didn’t know if she was a simple nanny or the mother) as if with a piece of plaster. The young woman was writhing on the ground, screaming in terror and pain. No one intervened.

Among the most vivid memories, of course, is having lived for a few months in a country at war. It was the Cyprus conflict in 1974. In the evenings, there was a curfew, and everything had to be barricaded. In the streets, many tanks were waiting to be repaired, their tracks broken.

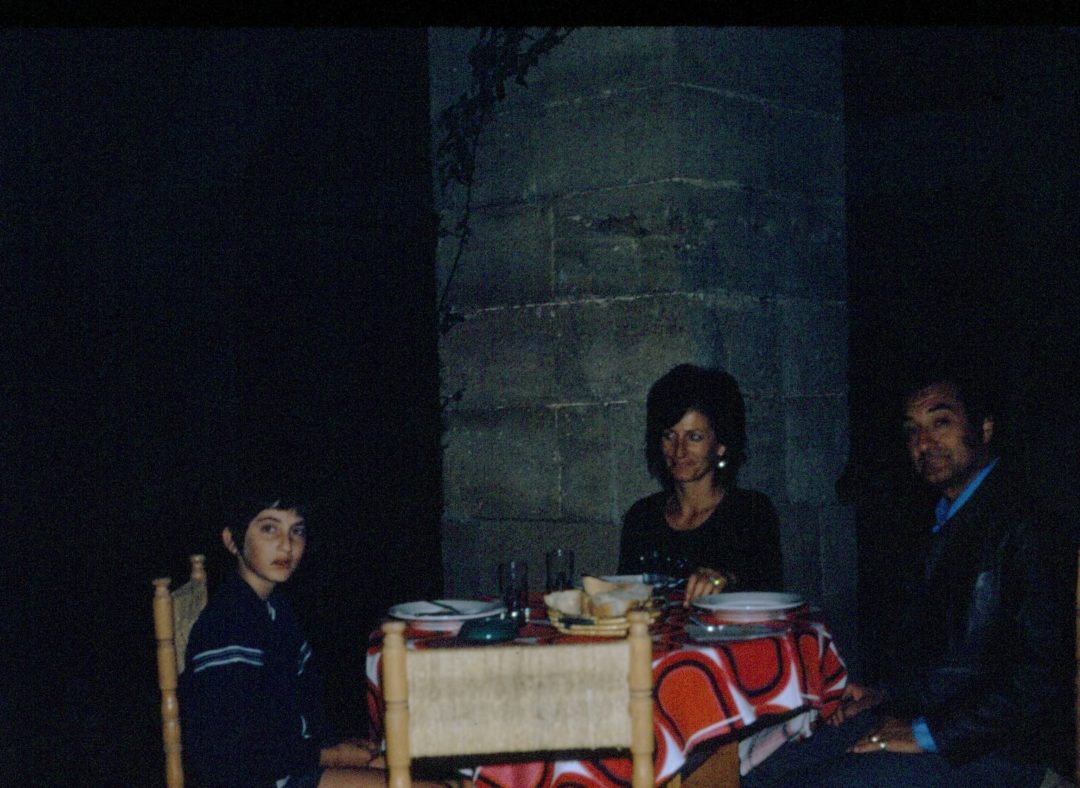

We were in France when this war was declared. Nonetheless, my father decided to return—home to Turkey—by road since all other means of transportation were impossible. He didn’t even know if the border was open. Yet, he set out to resume his work, taking his wife and child with him on a 3,000 km journey through the Eastern Bloc countries.

It would probably be unthinkable nowadays. We entered Turkey through the Bulgarian border, near Greece, in Edirne. It was evening, and because of the curfew, my parents decided to stop at a caravanserai. Due to the war, there were no other guests (except us), nor any lighting. Nonetheless, the manager agreed to turn on the lights just long enough to take the photo I’ve used to illustrate this article.

At that time, paved roads were still quite rare. I remember witnessing the construction of the first paved road between Bursa and Istanbul. Before that, it was just a dusty dirt track, on which we nearly got killed in our R16. A truck’s wheel brushed—literally, its body was scraped down to the metal over a few centimeters—our right rear wing, and I had plenty of time to see it just inches from me. My father had attempted to overtake the truck, which at the same time was passing a horse-drawn cart, while a car was coming head-on at the same moment. So, there were four vehicles coming abreast on a track designed for only two. Fortunately, the stabilization work for the road construction had made that spot a bit wider.

I am not talking about roads leading inland. It’s not for nothing that all the R12s sold at the time were equipped with reinforced shock absorbers and a protective metal plate under the engine.

Nonetheless, this situation quickly changed, and I believe most major roads had been paved by the mid-1970s. My memory is a bit unclear on this point.

All this to say that traveling on the roads was not without risks. Most people had no notion of road safety, and the concept of stopping distance was foreign to them. Someone could very well decide to cross in front of your car, assuming you would stop. Additionally, killing someone—especially a child—in a village was at best certain imprisonment and at worst lynching by the local population.

I remember a man who one day rushed towards our car and jumped onto the back seat, yelling at my father to start the engine. A furious crowd was chasing him. It seems he had run over and killed a child.

I come to the two memories that have left the most lasting impression on me. They are two road accidents.

Warning: Sensitive souls should refrain.

I did not witness the first accident directly, but it had just happened when we arrived. A bus had fallen from a bridge into a river below. I did not see any bodies; they must have been trapped inside the bus, which was visible completely crushed.

I remember the colors.

It was spring, and the grass was green. By the water’s edge, on the grassy plain below, women watched the shocked accident. They were all dressed in black. In the distance, the river flowed with a beautiful brown color. And just below the bridge, over a distance of about 50 or 100 meters, it was red—completely red.

The second accident, I almost witnessed it. I say “almost” because I was turned away from the scene at the moment of impact. I turned around after hearing the sound of the brakes and screams of terror.

A woman and her daughter, underestimating the stopping distance of a vehicle, decided to cross just as a truck was approaching. It was unable to avoid them. When I turned around, I saw the two bodies being torn apart. At the moment of impact, something had splattered and crashed a few meters from me, maybe three or four. I looked… it was a brain. Almost intact. This image has never left me, and I don’t think I’ve often shared this story.

Pour terminer sur un souvenir plus drôle, il y a eu également l’histoire de cet homme qui vivait – seul pensions nous – dans une cabane située dans un champ d’Olivier en bord de mer. Nous avions l’habitude de pique-niquer sur la plage jouxtant son champ. Il nous demandait quelques pièces comme droit de passage sur sa propriété. Si d’aventure, il n’était pas là lors de notre arrivée, il venait sur la plage réclamer son obole.

Ce jour-là des touristes de passage – c’était encore rare à l’époque – sans doute rassuré par notre présence ont décidé de venir bronzer à quelques pas de nous.

L’homme est donc venu et leur a également demandé sa dîme. Les touristes n’ont-ils pas compris ou voulu comprendre, je l’ignore ? Mais ils ont refusé de payer. L’homme furieux est reparti en hurlant. Quelques minutes plus tard, nous l’avons vu sortir de chez lui, cartouchière en bandoulière, fusil à la main avec.. Deux femmes – dont nous n’avions jamais soupçonné l’existence – s’agrippant à ses jambes en se laissant traîner par terre et hurlant : ne les tue pas, ne les tue pas !

To end on a funnier note, there’s also the story of a man who was living—alone, we thought—in a small cabin in a field of olive trees by the sea. We used to have picnics on the beach next to his field. He would ask us for a few coins as a toll for passing through his property. If, by chance, he wasn’t there when we arrived, he would come to the beach to demand his toll.

One day, tourists passing through—something quite rare at the time—probably reassured by our presence, decided to come sunbathe just a few steps from us.

So the man came over and also demanded his tax from them. I don’t know if the tourists didn’t understand or chose not to, but they refused to pay. The man, furious, left shouting. A few minutes later, we saw him come out of his house, with a bandolier over his shoulder and a rifle in his hand, with two women—whom we had never suspected existed—clinging to his legs, being dragged along the ground and shouting: “Don’t kill them, don’t kill them!”

No Comments