Cet article est également disponible en : Français

This is the translation of one article published in France in the N°51 of Road Trip Magazine.

I wake up with a start. All senses on the lookout, I listen at night. At such moments you can hear his heart beating and I have to wait a moment for him to calm down. Slowly, I grab my knife, which I always keep handy when I camp. The same one I found on the ground along the banks of the Zambezi River, not far from Victoria Falls 15 years ago. I usually joke that its former owner must have been eaten by crocodiles abounding there.

But for the time being, my mind has little time to lose itself in memories. A hoarse breath fills the night. The animal, the beast is big. It was the food left in my bowl not far from the tent that attracted him. A branch cracks right next to me. It must be less than 1 meter away. I had hoped for a big dog, but the way it moves leaves little doubt in my mind: it’s a bear. Only the thin canvas of my tent separates him and me.

I plague: apart from my knife, I have none of my usual means of “defence”: two empty bowls to make noise to frighten night visitors and, more offensive, a bottle of insecticide which, with the help of a lighter, can turn into a small flame thrower. But here there are few mosquitoes: I didn’t buy any. Besides, I didn’t expect this kind of night visit.

I arrived last night in this volcanic crater, not far from Lake Van in Turkey: Nemrut gölü. I pitched my tent near one of the two lakes without knowing that the area was infested with bears.

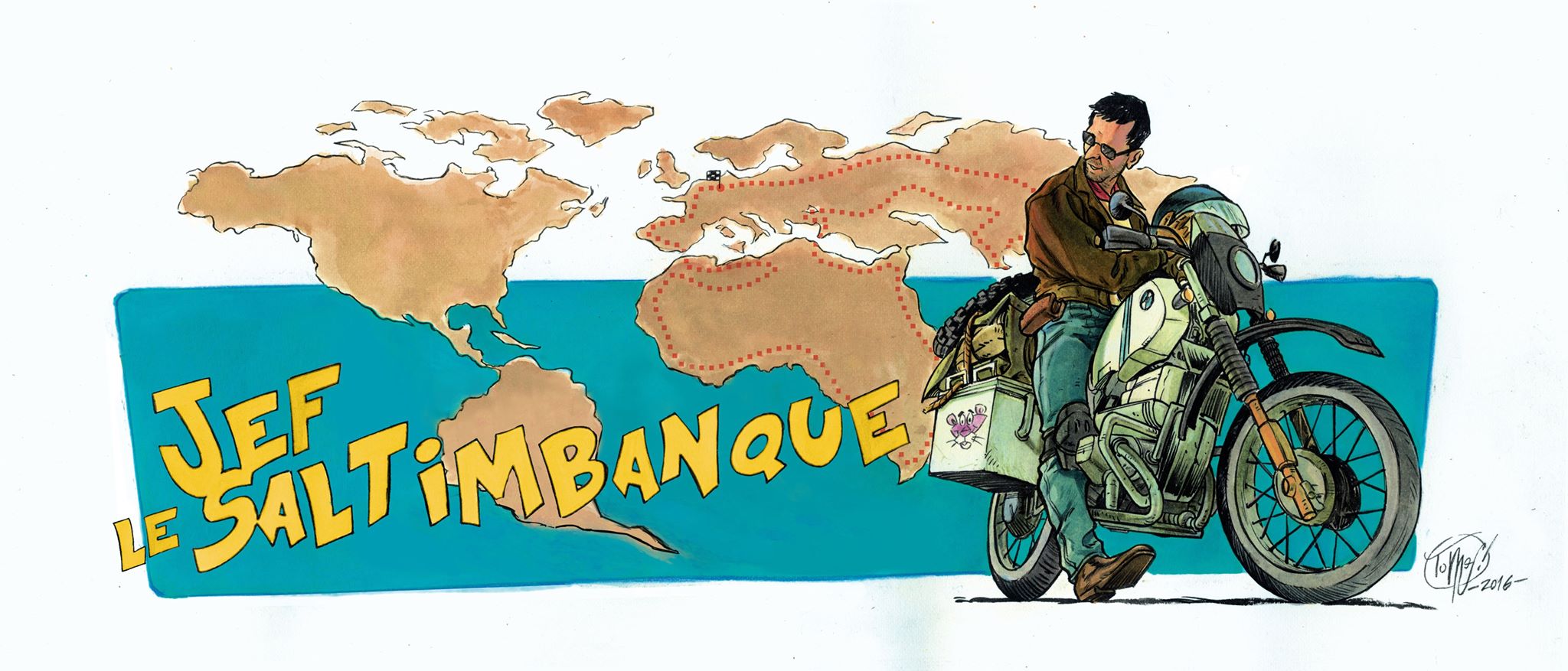

It has been almost two months since I left France already. The return is only expected at the end of 2019 and I still don’t know where my steps will lead me. No plan, just a vague and uncertain direction. A journey that I have named: “on the trail of storks”. My only constraints: the seasons and geopolitical hazards. Storks, they only have one. They don’t care about politics and visas.

This is my second trip. The first took place in 2003/2004. For 16 months I travelled all over Africa. The months before this second start were very different from those before the first. The first time, I had collected as much information as I could both to know what needed to be done and what needed to be known, but also to calm my doubts and fears. My friends, worried, were trying to stop me.

This time, I bought the equipment I knew was necessary, took some information about the seasons and customs formalities and my friends just wished me luck. However, a few months before the departure, a traveler friend, Luc, told me: “The hardest part is the second departure, because we know what we are going to have to face”. I was interested in his thoughts. It wasn’t how I felt. Yet he was right. My first trip was too far away. Time had done its work, I had forgotten what I had been through. But my body remembered it from the first few weeks after my departure and it took me a while to enter this second journey. The body was protesting and the mood was gloomy. It was the smell of water that brought me back to the journey. Because the water smells, didn’t you know that? That was a few days ago, I had just crossed a rocky desert in the middle of Anatolia. The heat was suffocating. The one that makes even flies give up flying. And then there was the valley. And with it the water and its smell. So is her freshness. It was at that very moment that I felt the joy of living. The journey then exploded within me, like a firework display. I was where I was supposed to be.

But it took me two months to cover a distance that other motorcyclists cover in just a few days. In fact, we don’t have the same tempo: they’re on vacation, I’m on a trip. Yet we travel the same road, we face the same difficulties, we have the same breakdowns on motorcycles, we have the same fears and the same or almost the same joys. They travel, of course, but they are not “travelling”. I think there is a term missing in the French language to describe long-distance travel. Some people call these “expeditions”. I find the term a little strong, even pretentious. A Jean-Louis Etienne, to name but one, made expeditions. But when you go on the road for several months or even years, you simply travel.

A trip begins after the third month. This is the time required for the moult to occur. So that the homo occidentalus turns into a traveler. A journey really only begins when you stop. We then cease to be a tourist eager for a kaleidoscope of sensations and images. We forget the watch and the only time that matters now is the time of the seasons. I have the memory of a Frenchman I met a long time ago. He was gone for two months, never came back. When I met him, he had just spent 2 years in Congo on behalf of UNHCR. One of his pleasures? Sit on a terrace and watch the crowd. The traveller makes slowness a virtue. Only slowness makes it possible to appreciate the distances and diversity of this world, only slowness makes it possible to cross eyes and smiles. Slow is a guarantee of intensity and encounters. The traveller is a contemplative.

He is also someone who refrains from judging. Montaigne, who loved to travel around France on horseback, said that when travelling, you shouldn’t “get carried away with yourself”.

When you leave, it is not enough simply to say goodbye to your family and friends, you must also and above all let yourself go, undress from what you believe to be right or wrong, right or wrong, right or wrong in order to recover the naivety and permeability of childhood.

“If you think like me, you’re my brother. If you don’t think like me, you are twice my brother because you open another world to me. “said Amadou Hampâté Bâ. The other, the one we do not yet know, the one we meet on the way, the one in front of whom we leave by closing the door of our home, whether he is a prince or a beggar, this one opens the doors of another universe, another form of thoughts and values. And the stranger he is today will become our brother, our companion, with whom we will share bread and laugh despite sometimes the language barrier. In the latter case, vodka can help.

Laughter and smiles too. They are even the traveller’s sesames. They open doors and hearts. It is with a smile that we obtain a roof over our heads for the night or that much desired visa. He disarms the anger of this irritated policeman and softens the mood of this overzealous official. But above all, and most importantly, it opens the doors to friendship and sharing. Its language is universal and does not need to be translated.

The smile is the traveller’s weapon, his viaticum and his best ally.

You don’t become a traveller without becoming fatalistic. One cannot go without the other and it is quickly understood that galleys are in fact only opportunities. When travelling, no assistance included in your insurance contract, no toll-free number: you are alone in front of yourself. But it is precisely this that opens the doors of possibility. It was because my shock absorber gave way that I met Henrick and Mwajabu his wife in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania. They’ve been friends for 15 years now. It was because my clutch cable broke that I met Arsen the Armenian and spent a memorable evening toasting vodka with him and his friends. It was a fall in Mbabane, Swaziland, that allowed me to discover the joys of picking mushrooms on the heights of the nearby mountains alongside one of the only French people who lived there at the time.

A trip is like a hot air balloon flight: you know when and where it starts, you have a vague idea of the general direction, but you never know where and when you will land. Or what’s going to happen next. My old flying teacher once landed in front of a house in Switzerland in the middle of winter. A woman came out and offered him hot coffee. She became his wife.

In the end, travelling is simply accepting to be carried by the wind. To let fate come to you and trust your lucky star. Travelling is letting go.

No Comments