Cet article est également disponible en : Français

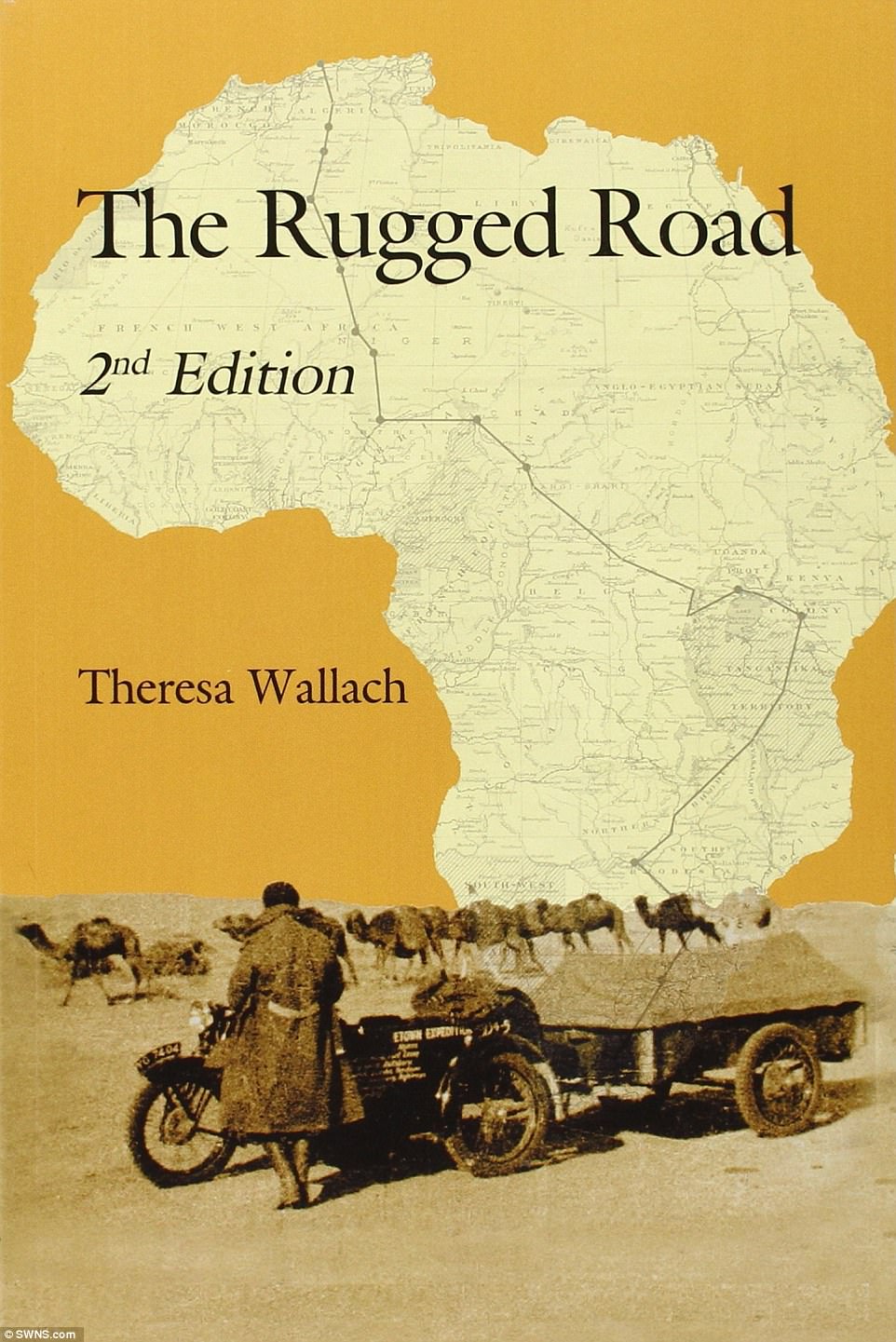

In December 1934, two Englishwomen leave London on a 600 cc Panther motorcycle.

Their objective: to cross Africa from North to South. Nobody before them had dared to attempt such an adventure.

Once upon a time there were two young women. The first one is called Theresa Wallach. The second was Florence Blenkiron, but she was often called “Blenk”. They are friends and the same fervor animates them, that of the motorcycle. They are both passionate about competition and mechanics. One of them is even an engineer. They are carefree, young and enjoy life to the fullest, refusing to conform to the stereotype of what a “proper” young woman should be in this rather conservative England of the 1930s.

One day Blenk confides to Theresa that she is thinking of going to Cape Town where her best friend has just settled. But at that time, no plane. Such a trip is only possible by boat and takes several months. So, out of the blue, Theresa said to him: “What if we went on a motorcycle? “Don’t be funny”, Blenk answers immediately, so much this idea seems absurd. However, just after she continues by saying: “would you come with me? This is how this adventure started: by the desire of a young woman to go and see her best friend on the other side of the world and the half-hearted challenge of another of her friends.

Very quickly, they understand that they can only count on themselves. Nobody believes in their project. Citroen’s Croisière Noire [1] is just 10 years old, and such a crossing required no less than 8 specially prepared tracked vehicles. So, to do the same thing on a motorcycle, and by two women on top of that? The idea seems crazy. However, through tenacity, they finally convinced a manufacturer to join the adventure: the bike would be a Panther 600cc Model 100 Redwing, a model that had just been released. Little by little, the project takes shape. There are two of them, so they decide to add a sidecar to their bike. The brand Watsonian joined the adventure and manufactured the sidecar and a trailer. The crew thus constituted will be baptized “The Venture”. Some equipment manufacturers also join the project, such Primus which will provide the stove, and on December 11, 1934, they leave London with the handlebar of their motor bike duly escorted by police officers charged to remove the crowd of onlookers come to attend this extravagant departure. A funny detail: in their preparation, they forgot to bring a compass and so they took the road to the South without a compass.

The adventure begins in France. The weather was rainy, and they stopped in a restaurant soaking wet. They are dressed and coiffed in a masculine manner and the waiter remarks to them, in perfect English, that “gentlemen must wear jackets”. They replied, “Really? That day, the menu ordered at random was a dish of frog legs. The exoticism had already begun!

The trip to Algiers went smoothly, but at that time, the few hotels were quite expensive. In order to save money, they decided to have their meal in secret in their room after having bought victuals in town. They carefully hid the surplus from the eyes of the room service. The next day, when they returned from a trip to the city, the receptionist informed them that they had been assigned a larger room. They find all their belongings, including food, carefully “hidden” in the same places as in their first room.

Algiers is a crucial step for the continuation of their project. Indeed, they had to convince the colonial administration to accept to let them pursue their crazy enterprise and thus to cross the Sahara desert, that is to say approximately 3000 km between Algiers and Agades interspersed with 6 military posts held by the Foreign Legion: Ghardaia, El Golea, In Salah, Arak, Tamanrasset and finally In Guezzam. This crossing was still considered impossible except by camel, and it is only 2 or 3 years that buses cross it regularly, and this only in winter because of the unbearable heat of the summer. After much procrastination, the permit is finally granted to them, with the payment of a permit worth 400 francs. They were also informed that if it was necessary to rescue them, they would be charged 4 francs for each kilometer traveled by the search teams. And again, the rescue teams do not leave the official track. It was up to them not to get lost!

They leave Algiers the day after Christmas 1934 around 10 am. The main street is invaded for the occasion of a huge crowd come to attend the departure of these two Englishwomen a little crazy. Some motorcyclists make the road with her until Blida. The final farewell will be done around a table of a small café. Their ephemeral friends then turn back. They are now alone. In front of them, the dreaded Sahara. And the unknown.

They have 5 days to reach Ghardaia, the first relay post, about 600 km away. After this time, the rescue will be triggered. However, they quickly understood that in the desert, time is no longer counted in hours, but in available water. And they only have 20 liters of water and 40 liters of gasoline. Very quickly, these two young girls, more used to the green English meadows, acclimatize themselves to this harsh desert. In the evening, it becomes both their living room and their bedroom. And for ceiling, they have only the celestial vault.

When they arrive in Ghardaia, they will have to perform tasks that will be repeated at each relay station: wash their clothes, repair what needs to be repaired, get supplies for the rest of the journey and finally, convince the station chief to let them continue. A bit like the captain of a ship, he is the only master on board and he doesn’t care about the authorizations granted in Algiers. Each time the same scenario will be repeated: after a warm welcome, even admiring, it is announced to them that the continuation is even harder and that it is better to give up. Each time, despite everything, they succeeded in convincing a concession to security: they had to leave the post 5 days before the next SATT bus[2] so that the latter could rescue them if necessary.

So they continue. The sand becomes softer and softer, the dunes higher and higher. In front of them, the corrugated iron which causes vibrations destroying the material alternates with the fech-fech. When the trailer gets stuck in the sand, they use the motorcycle as an anchor and free it with a system of ropes and pulleys. And vice versa. Frequently, they ride at night by the light of the moon, in order to spare the engine, and themselves, from the oppressive heat of the day. Between Golea and In Salah, the attachment of the trailer breaks. It is the catastrophe, they have no spare part. Desperate, they scan the desert. Not far away, a car wreck finishes rusting. Miracle, they find a fastener and hurry to unbolt it. Alas, the French standard does not correspond with the size of their English material, and the male and female parts do not fit together. Armed with two files, they set out to solve the equation. The night caught them before it was over. One day is enough, they decide to finish the next day. In the meantime, they take out a bottle of Cognac and get drunk under the starry sky of the Sahara. Gradually, they become girls of the desert, learning to bake bread in the sand in the Tuareg way, or acquiring a goat skin pouch, allowing the conservation of water at a much more pleasant temperature than their European gourds.

They arrive in Tamanrasset a little after mid-January of the year 1935. The inhabitants are intrigued: it is the first time that a motorcycle arrives there and they are received with honors by the legionnaires in place. A meal was even organized for them and for the occasion the local French baker made some pastries. But then came the cold shower: the commander categorically refused to let them continue. According to him, they will not pass with the trailer. They must resolve to let it leave on the roof of the next bus. They will find it in Agades. They have to optimize their loading in the side-car, which is not an easy task. Water and gasoline are once again priorities. They also decide to take advantage of the baker’s presence to make an excellent bread which will be used as basic food on the next stage. After a clever conversion between English units and the metric system, they order the necessary flour from the baker so that he can make the desired bread. It is only at the moment of taking delivery that they understand that they were mistaken of one decimal: instead of the 5 expected breads, there are about fifty!

They arrived at In Guezzam on January 20. It is the last relay post before Agades and the biggest part of the Sahara is now behind them. However, it is on this last section that they will undergo the first big damage of this journey. The engine of their faithful steed breaks. They are alone. The evening falls. After a few moments of disarray, they decide to continue by pushing the motorcycle, fortunately lightened of the trailer since Tamanrasset. It will take them a whole night to cover 40 km with the strength of their arms and calves. In the early morning, they arrive near a Fulani village where they find water, food and help.

The next day, after a well-deserved rest, they took to the road again, pulled by a horse for more than 100 km and it was in this burlesque crew that they entered Agades in early February 1935. They stayed there for a month waiting for the spare parts necessary for the repair and it was only on March 4 that they were able to take to the road again.

The adventure was far from over. In Nigeria, they will see a disturbing slave market. In Chad, not far from the Chari River, they suffered the second major damage of the trip: the hub of the front wheel broke. Impossible to push this time and they have to wait for a vehicle to pass. In the meantime, the villagers, people of fishermen, feed them and come at night to dance and play the tom-tom by the light of the campfire. When two or three days later, a truck finally arrives, they abandon the motorcycle on the edge of the track for more than a month, the time to have the wheel repaired.

The rainy season arrives and after the sand of the desert, they have to face an even more terrible enemy: the mud. They cross a thousand rivers under the eye of the crocodiles and other hippos. Soon, they enter the thick forest of the Congo, which has not yet been mapped. It is the complete unknown. Theresa celebrates her 26th birthday with the pygmies and their tom-toms. They passed by the place where Stanley had joined Livingstone just 64 years earlier, and it was in triumph that they finally arrived in Cape Town on July 29, 1935 after an epic journey of more than 22,000 km.

No one knows what happened then, but Theresa was sick and weakened and left for London by boat. Without money, she will live for a while in the street. Blenk, with the handlebars of a second motorcycle, the Venture II, undertakes the ascent in September 1935. She arrives at Kano, at the doors of the desert, in January 1936, but this time, being alone, it will be impossible for her to obtain the authorization to cross the Sahara and it will be necessary for her to solve to put the motor bike on the roof of a bus. She returned to London in April 1936 after 16 months of adventure.

Thereafter, each of them lived exceptional lives, both participating in the war effort as mechanics, drivers or trainers of motorcyclists in North Africa. Theresa rode her motorcycle across America and was one of the founders of WIMA[3]. Blenk lived in Australia and India.

Blenk died in 1991 at the age of 86 and Theresa in 1999 at the age of 90. They never saw each other again, but I like to imagine that their story is still told some evenings, like a tale, by griots by firelight in the deep forests of the Congo, or under the starry sky of the Hoggar desert.

[1] In 1924, the “Black Cruise” carried out by the Citroën teams was the first crossing of the whole of Africa carried out with a motorized means.

[2] Société Algérienne des Transports Tropicaux, created in 1933 by Georges Estiennes. The first trans-Saharan bus company that made it possible to travel from Algiers to Kano over a total distance of 3760 km.

[3] Women’s International Motorcycle Association.

No Comments